What is inflation and how does it affect us?

Money Talk is intended to inform and educate; it's not financial advice. Affiliate links, including from Amazon, are used to help fund the site. If you make a purchase via a link marked with an *, Money Talk might receive a commission at no cost to you. Find out more here.

We talk about inflation all the time in the context of the cost of living crisis and the economy, so you may well be wondering “what exactly is it?”.

The answer is both simple and rather complex as there are technically three definitions of inflation.

What is inflation

Inflation is defined as the rate at which the prices of goods and services increase year on year.

You’ll experience it as the cost of living increasing over time.

Economists like a healthy bit of inflation – hence the Bank of England’s 2% target – because it shows growth in the economy.

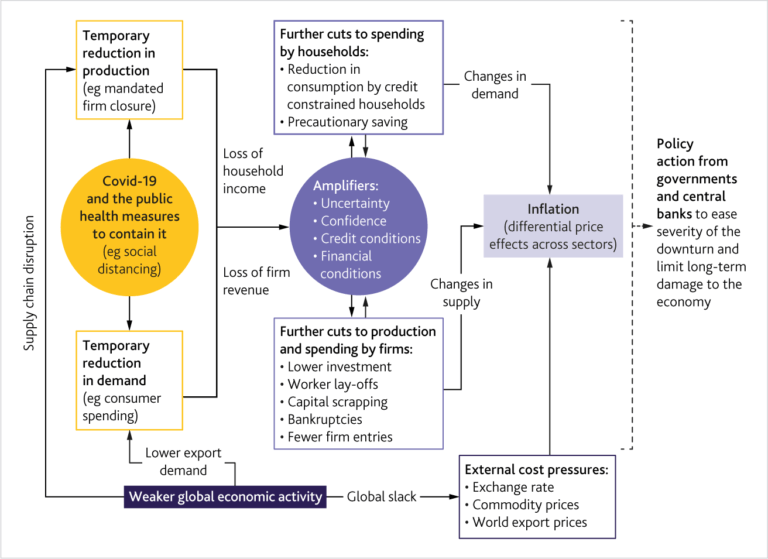

However, if there’s too much inflation then the cost of living might spiral out of control, and leave more people in debt.

And if there’s too little inflation or even deflation, it’s an indicator we might be moving towards a recession. And that’s no good either.

How inflation is measured

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) provides three separate measures for inflation each month:

- Consumer Price Index (CPI)

- Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH)

- Retail Price Index (RPI)

All three measures of inflation are calculated by tracking the price changes of a “basket of goods”.

This basket contains items that the government thinks typical British people buy, ranging from food and drink to travel and clothing.

Each items is weighted according to how important they are in the average household’s expenditure.

For example, housing and transport eats more into the family budget than education and health, so the latter two are given a lower weighting, meaning changes in their prices doesn’t influence the overall inflation rate as much.

The items in the basket change over time – things get added and things are taken away.

What’s in the basket also differs between RPI and CPI (CPIH is just CPI with cost of housing factored in).

Each month, the ONS collates the average prices of everything in the basket of goods (approximately 180,000 prices for around 700 items), and compares them to previous year’s figures to work out the percentage change.

If there’s an increase, you have inflation. But if the figure is negative, you have deflation.

Three measures of inflation

To really complicate things, all three measures of inflation are currently still in use.

CPIH is what the UK government uses to track inflation.

CPI is what the Bank of England uses for their target, which could influence how they adjust interest rates.

And RPI is used in long term contracts, including some house leases and cost of rail fares.

The RPI and CPI use a similar basket of goods (albeit categorised differently), and each includes items that the other doesn’t.

The CPI and CPIH contain university accommodation fees for example, but RPI doesn’t.

Meanwhile, the RPI basket includes estate agents’ fees, which isn’t found in the CPI and CPIH measures.

And it’s worth noting that the items in the basket does change over time.

It means what gets chosen for this imaginary basket can be a fascinating insight into our society and how consumer tastes change over time.

Who benefits from inflation?

In general, it’s accepted that borrowers benefit from inflation.

That’s because inflation eats into the value of money – £100,000 in 10 years time won’t be able to buy you nearly as much as it does today.

So when there’s high inflation, it’s cheaper for borrowers because what they’re paying back over time isn’t worth as much as the money they borrowed.

Of course, in reality inflation drives up the cost of living for everyone.

So while it might be cheaper to borrow, it might also be more difficult to pay back the money you owe due to higher costs everywhere else.

This post was originally published in February 2021. It was updated in July 2024.

Pin this for later